Fake News:

Can anybody stop it?

Intro

THERE was something awkward when an American online news editor coined the term “fake news” in mid-2016 to point to a cluster of rambunctious websites posting fabricated stories that caught thousands of views on social media site Facebook.

It generated wide use meant to describe collectively false, often sensational, information disseminated under the guise of news reporting. It would later come not just as a news story, but also as an altered photograph, an art card, or a meme, which is anything but true. Some could be labeled as “half-truths,” but all were meant either to deceive or help form public opinion favorable to a certain man, group or organization.

At first, some found fake news amusing, but its tremendous rise, obviously calculated and well-planned, posed problems to legitimate news organizations, though even their members and other various respected organizations that began to utilize social media, particularly Facebook, at times fell prey to similar misinformation (or disinformation if you wish).

To help understand fake news, Dr. Edson Tandoc of Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information at Nanyang Technological University, led a group of college professors in Singapore in reviewing 34 academic articles published between 2003 and 2017. Their study resulted in a typology of types of fake news: news satire, news parody, fabrication, manipulation, advertising, and propaganda.

These definitions were based on two dimensions: levels of facticity and deception. “Such a typology is offered to clarify what we mean by fake news and to guide future studies,” said Tandoc, who obtained his doctorate in Journalism at the University of Missouri, to introduce the result of their review.

Whatever you call it, it is wrong information.

No such thing as fake news

But journalist Ellen Tordesillas of Vera Files, an accredited Facebook fact checker, hated the term “fake news,” for it makes a mockery of legitimate news and the journalism profession. “In fact, it is not only awkward to use the phrase fake news, it is an oxymoron,” Tordesillas said. “If it is news, it is not fake.” For all the shortcomings of news organizations, what they call and publish as news is legitimate, culled from rigorous process of information gathering and double checking, including layers of editing—never mind some occasional lapses.

‘What fake news? No such thing. It is an oxymoron’

Ellen Tordesillas

Tordesillas is right, and perhaps it is only appropriate that news organizations disown and distance themselves from fake news, or at least, on social media. Mainstream media err, wrote another veteran newspaperman turned aggressive online advocate Philip Lustre, but they can be held accountable; they correct and issue errata. Sources of fake news, most of them of unknown origin, he added, don’t.

Mainstream media err, but they can be held accountable; they correct and issue errata.

Philip Lustre

Never—primarily because the men and women behind “fake news” wanted to deceive, to promote a person, group, or idea, and to shape public opinion the way they saw fit, even if was contrary to reality or facts.

DDS, pro-gov’t bloggers

In the Philippines, some of these fake news sources remained almost faceless—until Facebook announced the shutdown of several of what they believed were fake accounts, all of which were supposedly supportive of President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration.

Against this backdrop, Lustre said other fake news sources were pro-government bloggers and websites. Tordesillas and Bulletin columnist Tonyo Cruz, a long-time social media advocate, were once more categorical: In the Philippines, the Palace was the prime source of fake news.

“They have lots of money,” Lustre said. “Isn’t it obvious?”

Tordesillas and Cruz had listed in their columns a long litany of fake reports emanating from the Palace, or its supporters, collectively called DDS, or Diehard Duterte Supporters. Other people blame the Palace likewise for its failure to stop fake news.

“I always believe that technology is neutral. Any technology is neutral, it’s use depends on the user. Kahit martilyo ‘yan, plantsa, TV, hindi iyan masama. Internet is neutral pero depende iyon sa gamit. Depende iyon sa gumagamit at paano niya gamitin. So ‘yung internet, ginamit ng pulitiko para i-replicate ‘yung trapo politics online which is esssentially ano ‘yung ginagawa ng mga trapos before. Iyung mga trapo before, nagmisinform, nag-disinform, nagrent ng crowds. Dati naman ang problem ng pulitiko sa Pilipinas nag-orchestrate ng public support. Nanghahakot ng crowd. Ngayon trolls na to manufacture consent for policies.”

Tonyo Cruz, Bulletin columnist

The Yellows, too

Not once did the Palace call for an “unbiased” fact checker, saying its critics, particularly supporters of the former President Benigno Simeon Aquino III and his Liberal Party (collectively called “yellows” or “dilawans”), had similar accounts.

Curiously, former Inquirer reporter JP Fenix during the time of President Corazon Aquino had made a similar observation. In a November 17 Facebook post, Fenix said “(he) blocked a few DDS today because of their self-righteous fakery. But don’t be cocky, dilawans. Your own self-righteousness was the cause of the rise of the DDS to start with.”

A television reporter perceived to have been so close to the family of former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo believed that he had been ganged up on many times by unknown netizens, all supporters of Arroyo’s successor, Aquino III, then the incumbent president, all trying to harass him with false accusations.

Cruz said fact-checking is not a matter of bias. It is the criteria Facebook has set to rid out fake news proponents and enablers—or what the platform calls “community standards.”

There were others in and out of government who have been reported to maintain their own accounts, too, to promote their principal. Many, if not most, were engaged in choreographed activities, especially before, during and after an election campaign.

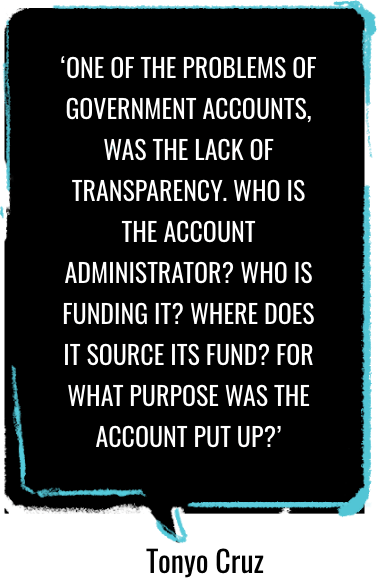

‘One of the problems of government accounts was the lack of transparency. Who is the account administrator? Who is funding it? Where does it source its fund? For what purpose was the account put up?’

Tonyo Cruz

Facebook said it has continued to improve its ability to detect and block attempts to create fake accounts, which peaked in June when protesting students from University of the Philippines in Cebu woke up one morning and discovered that they had duplicate Facebook accounts. The school paper first reported about the dummy accounts a day after the police arrested three of its students and five other individuals while holding a protest action against the controversial anti-terrorism bill in front of the university campus in Cebu City. It created panic among government critics.

Facebook said it has disabled 1.3 billion fake accounts, within minutes after creation by the third quarter of 2020. “ About 99.3 percent of the accounts were found and flagged by Facebook before users reported them,” Facebook said in a report.

“Then, for content that does not directly violate community standards, but still undermines the authenticity of the platform, it reduces its distribution by demoting it in News Feed, significantly reducing the number of people who see it,” the report added.

Cyber Detectives

Surprisingly, an American cybersecurity Blackpanda in the Philippines has closed shop for seeming lack of government and private interest in cyber security.

Did you know?

While the government has learned to tap COVID tracers, it has not found value in fake news tracing. According to Gene Yu, Blackpanda CEO and founder, while the challenge of cyber security is so huge in the Philippines, the market is so small.

“There’s just so much cyber business ongoing and there’s such a gap in the Asia region. We also discovered as you pointed out that the Philippines is in its infancy when it comes to cybersecurity but the market was too small for us to quickly concentrate there like we did with physical security.”

Gene Yu, Blackpanda CEO and Founder

‘Infodemic’

“We are now suffering from a case of ‘infodemic,’” said Edson Tandoc, a former Manila-based newspaper reporter who graduated summa cum laude from the University of the Philippines in 2003, on the proliferation of fake news, in a YouTube presentation. “[This is] a pandemic of fake news, coming from all walks of life—young and old, rich and poor. And it has become very dangerous, capable of destroying one’s reputation and fortune—even lives,” he added.

“We are now suffering from a case of ‘infodemic,’”

Edson Tandoc

But fake news has nothing to do with people’s level of literacy, Tonyo Cruz stated. It is about the capacity of people behind fake news to deceive—especially those in government. They have the capacity, he added, to blast information; they have an army of trolls.

Fake News, Fake Newsman?

Still, politicians, professionals, civic leaders, students, and even newsmen, one way or another, have fallen to fake news. At some point, they were wittingly or unwittingly fake news enablers.

A newsman known for his unqualified support to President Rodrigo Duterte reported on his social media account that actress Julia Barreto, once rumored to have snatched somebody else’s boyfriend, was pregnant. The post easily spread, despite the newsman’s failure to present an iota of evidence. Barreto denied the report. One should have seen Barreto at that very moment. There was an upheaval in her soul.

The newsman later deleted the post and apologized, instantly making Barreto an anti-fake news champion.

Citizen Journalists

And there is always one fake news too many. According to Tandoc, this was a result of digitization.

“Citizen journalists were initially confined to blogging,” he said, quoting their study. “Online platforms provide a space for non-journalists to reach a mass audience. The rise of citizen journalism challenged the link between news and journalists, as non-journalists began to engage in journalistic activities to produce journalistic outputs.”

Not only did social media change news distribution, it has also challenged traditional beliefs of how news should look. Twitter, for example, became a perfect platform to quickly disseminate details about a breaking event. So quick, so short, yet so powerful, judging from the number of users.

The most popular social media platform, Facebook, has been reported to have more than 1.23 billion daily active users as of December 2016.

“While Facebook started as a site through which we can share personal ideas and updates with friends, it has morphed into a portal where users produce, consume, and exchange different types of information, including news,” the study said.

A survey carried out in the United States found that 44 percent of the population get their news from Facebook. “Social media sites are not only marked by having a mass audience, they also facilitate speedy exchange and spread of information,” the study added. Unfortunately, these social media platforms have also facilitated the spread of wrong information – in the quickest and widest way possible.

Did you know?

From January to August 2020, the Philippine National Police received and investigated 5,262 cybercrime complaints.

When Fake News Goes Viral

In another article, Tandoc and his student Mak Weng Wai wrote: “Online falsehoods work like viruses. They need to infect one vulnerable host who can then spread them to other hosts.”

It has been more obvious in this time of pandemic when people, forced to stay at home because of the lockdown, relied heavily on social media for updates.

“This pandemic has exposed many of our vulnerabilities,” the article said. “And one of them is our susceptibility to spreading and believing in problematic information, aided by the ease and speed of information flow facilitated by social media and messaging apps.”

In the Philippines, like in Singapore, there were too many confusing and misleading reports at the outset about how one could acquire Covid 19 and how to treat it. The confusion was probably one of the reasons that hastened the spread of the virus.

In Iran, where a flow of information has been on strict government control, some Iranians swallowed methanol after someone’s post in February went viral that it was good medicine against COVID-19. Results were fatal.

Tandoc said fighting misinformation was particularly crucial in a time like this, to protect not just one’s self and family, but also others in the community. This is why it is important for us to keep an eye on not only the public’s information behavior, but also the quality of information flowing through various channels, he added.

Covid Scare

Between March and October of 2020, Facebook displayed warnings on about 167 million pieces of content on Facebook based on COVID-19-related debunking articles written by its fact checking partners.

In April this year, Facebook put warning labels on about 50 million pieces of content related to COVID-19 on Facebook, based on around 7,500 articles by our independent fact-checking partners.

“When people saw those warning labels, 95 percent of the time they did not go on to view the original content,” Facebook told PhilStar Online.

Facebook said it has been working hard to improve the accuracy of information on the site. “This is a responsibility that we take seriously,” they said.

Across News Feed, Facebook follows a three-part framework to improve the quality and authenticity of information:

- It removes content and actors that violate its Community Standards, which enforce the safety and security of Facebook.

- Then, for content that does not directly violate Community Standards, but still undermines the authenticity of the platform, it reduces its distribution by demoting it on News Feeds, significantly reducing the number of people who see it.

Digital Literacy

Aside from its own army of fact checkers, Facebook has tied up with academics about how we can work together. It has launched a digital literacy and citizenship program called “Digital Tayo” in 2019. Digital Tayo’s learning modules cover topics such as safeguarding online privacy and safety; respectful digital discourse; how to spot false news; and being responsible for your digital footprint.

Finally, Facebook said it has tried to inform its users by giving them more context on the information they see on their News Feed. These context units are an example of a feature that gives people additional information, by sharing more details on the article and the publisher.

“We want to empower people to decide for themselves what to read, trust, and share. We do so by promoting news literacy programs globally and sharing tips to help spot false news, and informing people with more context about the posts they see [on their] News Feed[s],” Facebook said.

“This is a highly adversarial space, so we still miss things and won’t catch everything— but we’re making progress.”

Are you with us so far? Let’s check.