‘NEWS CAN’T BE FAKE’

Fake sites takedowns raise more questions

Facebook takedowns

WHEN Facebook announced in September that it had taken down networks of fake and pro-Duterte administration accounts and pages originating in China and the Philippines, reactions online were quick but highly divided.

Facebook explained these networks violated its policy against so-called coordinated inauthentic behavior, mostly observed in the way these fake accounts and pages, with hundreds of thousands of followers, spread false information to influence, if not interfere in domestic politics.

Yet it seemed this action brought about even more confusion on the problem of false information or fake news in the Philippines. Once again, people raised the question, what is considered fake news? How do we get rid of it?

Denied by gov’t, welcomed by critics

Advocacy groups and activists took it as a victory against false information being propagated by the Philippine military and police about critics of the Duterte administration.

In a tweet, Kabataan party-list representative Sarah Elago, who had been accused of being a member of the New People’s Army, lauded Facebook’s decision. “This is good news to all who have been targeted by state-sponsored disinformation,” she said.

However, President Duterte and his supporters found it offensive. They said Facebook was interfering in the government’s efforts to fight communism and maintain peace and security in the country.

They also believed Facebook was being unfair because, to them, critics were peddlers of false information themselves.

In a televised address, Duterte called out the social media giant: “What would be the point of allowing you to continue (in the Philippines) if you can’t help us?”

It’s easy to dismiss facts

But what is fake? And what is not?

In various interviews and fora, veteran newsman Vergel Santos said the two words “fake” and “news” shouldn’t be put or used together.

"News is something that's supposed to have happened,” Santos told a television interview. “And what fake news is, I suppose, is an occurrence that did not occur. I would prefer to use, probably, false information.”

The problem is not only to ferret out news from false information, he said. "You'll have to define not only fake news, but you'll have to determine the measure or the ‘fakeness’ of that fake news."

Santos and his younger colleagues, among them Ellen Tordesillas, Philip Lustre and journalism and communication teachers Jason Vincent Cabañes of De La Salle University and Edson Tandoc of Nanyang Technological University, condemned the use of the word fake to describe a news story published by media organizations.

This is especially because the perpetrators of fake news are some government officials, said Tordesillas in an interview with PhilStar.com. She has repeated this view many times in various gatherings.

“The worrisome part of this is that most of the sources of disinformation are being perpetrated by government officials on taxpayers’ money. And the number 1 source of fake news is President Duterte himself,” she told a Senate hearing.

Call it false info, not fake news

People are aware of rampant disinformation, the term Cabañes preferred to explain fake news. “So that’s actually the technical term that we use to talk about patently false information that’s deliberately created and disseminated to other people.”

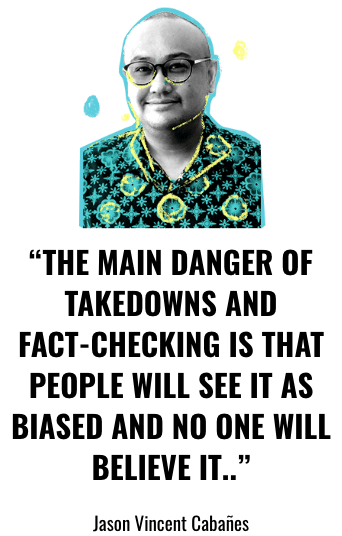

“The main danger of takedowns and fact-checking is that people will see it as biased and no one will believe it..”

Jason Vincent Cabañes

Cabañes said this terminology, not fake news, is more serviceable. “News cannot be fake, right? It’s either it’s news or it’s not news.” He differentiates disinformation from misinformation, which is when someone does not know whether or not something is true but shares it anyway.

He warned against using the term fake news because it blurs the line between what is news and what is not, which is the intent of those who produce disinformation. “The reason why fake news, alternative facts, these concepts are getting around is because the people who actually create disinformation push for these labels also. It lends them a bit of legitimacy.”

There is danger if a reader couldn’t tell one from the other, according to another senior newsman, Luis Teodoro.

On his blog, Teodoro said the production and sharing of false information has undermined informed citizen opinion— and decision-making on a number of issues, among them the Duterte regime’s supposed campaign against illegal drugs.

“Disinformation has been used to conceal the brutality of the Duterte “war on drugs” and the evils of the Marcos kleptocracy, as well as to support plunderers, mass murderers, and corrupt officials,” said Teodoro in a June 2019 post.

“Because it has reduced public discourse to who can mobilize enough online trolls and print and broadcast hacks to drown out the voices of reason, the inevitable question is still how “fake news” or disinformation may be best combatted.”

Fact-checking not enough

But Cabañes has some issues about fact-checking and the shutdown of some Facebook accounts it deemed fake, because of opposing claims which, he said, show inadequacies in the current steps being taken to address false information.

“The main danger of takedowns and fact-checking is that people will see it as biased and no one will believe it,” said Cabañes, who took his PhD in Communications Studies at the University of Leeds.

But the issue is not just about bias, said Manila Bulletin columnist Tonyo Cruz. “It is about the criteria set by Facebook against fake accounts.”

To stop the spread of false information, Facebook partnered with fact-checkers around the world that are certified by the non-partisan International Fact-Checking Network. In the Philippines, there are only two verified fact-checking organizations so far, namely VERA Files and Rappler.

As fact-checkers, VERA Files and Rappler help Facebook in fighting false information by rating and reviewing the accuracy of posts in the Philippines.

More local consultants needed

Cabañes said Facebook’s current fact-checking program, just like many fact-checking efforts, is a good start, but it needs to engage more consultants and local stakeholders who could help the social media company in properly implementing its policies against false information in the Philippines.

“The Philippines is a very special case. They need to pay attention to what’s going on and create that broad-based coalition for consulting when it comes to takedowns and labeling things as disinformation or not,” Cabañes noted.

Weaponizing disinformation

Instead of allowing truth and facts to prevail, however, politicians and their supporters resorted to using such disinformation to get the upper hand, Cabañes said.

For much of the debates and discussions online concerning Philippine politics, especially since the rise of Duterte to the presidency, the DDS or Diehard Duterte Supporters and the dilawans or ‘yellows’ supportive of Vice President Leni Robredo and her Liberal Party have been the main opposing camps.

Cabañes explained both sides point at each other as the source of disinformation. “Politicians feel that if they don’t engage in disinformation, they’re going to lose the game, right? So a lot of politicians, whether they like it or not, have gone into the game of disinformation.”

“…the DDS will say, it’s the dilawans. The dilawans will say, it’s the DDS doing disinformation.”

Cabañes also mentioned that when one party presents information, the other party already has a particular perspective and interpretation set against it. “People are aware but they have different attributions. They always push (the responsibility) to the other camp. To speak concretely, the DDS will say, it’s the dilawans. The dilawans will say, it’s the DDS doing disinformation.”

Ad, PR agencies behind disinformation?

In a 2018 public report written for the Newton Tech4Dev Network by Cabañes and Jonathan Corpus Ong, Associate Professor of Global Digital Media at the University of Massachusetts, strategists from advertising and public relations agencies were identified as “chief architects of networked disinformation campaigns” in the Philippines.

“Having interviewed disinformation producers, I can tell you that the people who lead these campaigns are really geniuses,” Cabañes shared. “And that’s what scares me. They’re really good [at] what they’re doing.”

Cruz made a similar observation. “Why are these people silent about this fake news[?] They run troll [farms], write praise releases for people,” he told PhilStar in a Zoom interview.

Cabañes noted that these strategists included former media people and former journalists, who are essentially experts in creating materials that appeal to many Filipinos.

“What disinformation producers do is they’re so good at getting the pulse of people, kind of understanding, how do people see things? And then they connect with that and then they weaponize that. They amplify the sentiments of people in a very toxic way, in a vitriolic kind of way.” Indeed, there have been countless viral posts online regardless of their credibility and accuracy.

“And I think that’s what makes our situation quite distinct, that not only is disinformation very innovative here but that it’s really hitting on how people perceive the world and perceive our society.”

Jason Vincent Cabañes, Professor, De La Salle University

Reinforcing fact-checking with narratives

This is precisely why, for Cabañes, fact-checking alone will not address disinformation. It is not just about getting facts right, he said. It is also about shaping how people see the world.

“The bigger dynamic that’s going on is that people have stories in their head. I call these social narratives. And it’s these social narratives that they use to interpret the information or disinformation that they get online,” Cabañes explained.

Are you with us so far? Let’s check.