Celebrities:

Who is behind fake news? Who to turn to?

Intro

THE Internet is an immensely powerful platform for communication. Millions of people can post anything at any given time and an equal number can read an opinion or a story or even view a photo just moments after it was posted. And in just a snap, anyone’s post can get viral online for all the world to see.

But it has been said that with great power comes great responsibility.

The Internet as a tool for communication does not filter content online. In effect, it is easy for people to post wrong information online and get away with it through engagements and reactions.

With the absence of proper vetting, wrong information and fake news can spread online in a blink of an eye.

Richard, a chemical engineer from Marikina City, became the victim of a fabricated photo which went viral online.

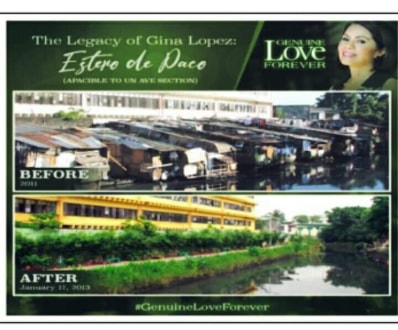

Richard is the Project Engineer assigned to rehabilitate Estero de Paco in 2012. Being hands-on for the project, he has practically memorized how the estero looked like before and after the rehabilitation.

One day, as Richard was browsing through his social media news feed as he usually does every day, a familiar photo caught his attention.

Two photos had been put together side by side with captions “Panahon ng Disente, Pasig River Aquino Term” on the one hand, and “Panahon ng Bastos, Pasig River Duterte Term” on the other.

This was posted on a Facebook group supposedly created by supporters of a government official.

Being so familiar with the material, Richard said that the photos were culled from original pictures of the Estero de Paco before and after the rehabilitation program he headed in 2012.

“I know for a fact that their claim was fake for I was the project engineer, and we completed the project in 2012, which is inimical to their claim of finishing it during the BASTOS time!” Richard said in an interview with Philstar.com.

Friends and other people involved in the project also saw the post and shared the same sentiment as Richard.

“The feeling was enraging.”

Richard Peñaflor

As Richard explained, the fabricated photos were originally owned by Kapit Bisig Para sa Ilog Pasig, which started under Gina Lopez’ ABS-CBN Foundation, and the now defunct Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission.

“Naniniwala kasi ako na ang isang mali or fake na laging ginagawa is nagiging tama kalaunan! Kaya it has to be corrected right there and there!”

Richard created a Facebook post in turn explaining the truth behind the two photos. His post went viral with at least 5,000 people who read, reacted, and shared.

The fabricated photo was eventually taken down from the supporter’s page.

He also shared the original photos of the Estero de Paco during the rehabilitation project.

“Anybody can be a victim of unscrupulous people, especially these days when trolls earn from purveying fake news, because there are supporters and fans (funds) for fake news!” he said.

After this experience, Richard realized the need for verifying posts online before believing and sharing.

“Share and patronize only what is absolute[ly] true. If we are not sure of any news or photos, take time to research on it or ask an authority about it. Lastly, give credit where credit is due!” he advised.

News personalities fall victim too

Famous people are not spared from the threats of fake news. In fact, their wide reach online makes them more vulnerable.

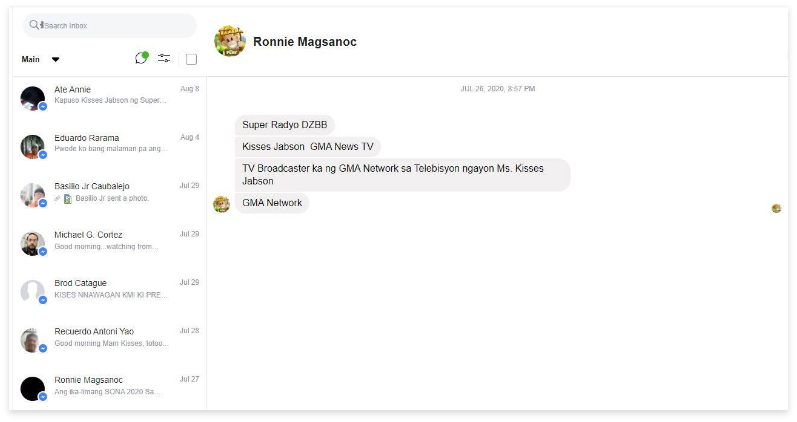

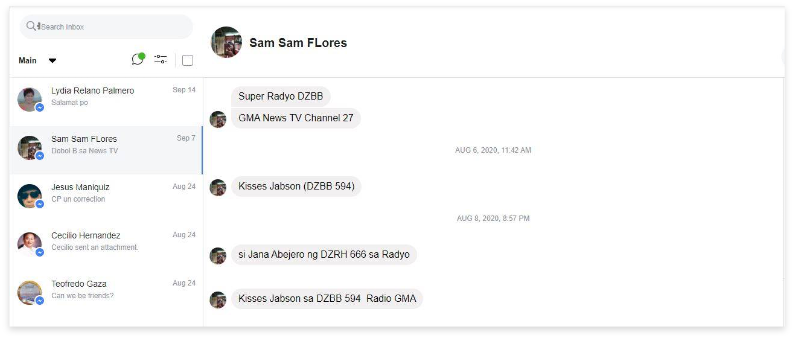

For radio anchor Kisses Jabson, government agencies could play a big role in running after fake news purveyors. In her opinion, there should be a knowledge campaign on how, where, and to whom one can report when one falls victim to fake news.

This was based on her personal experience.

Jabson did not have the guts to go to the authorities when she fell victim to fake news thinking that law-enforcement agencies had better things to do than act on her “petty” complaint.

Random strangers sent messages to Jabson’s Facebook telling her about a radio show on another station she purportedly hosts.

These messages came from accounts named after news personalities from other news outlets.

“Nagumpisa yun ng meron mga nagmemessage sakin, actually iba iba eh. Iba-ibang tao. Meron Annie, merong Toni, parang may pangalan pa nga yata ng basketball player. Ang Unang tinatanong sa akin kung anong oras ang programa ko sa DZBB. ‘Yung ang una. Ang sabi ko, hindi po ako taga, minsan kasi may mga listeners na yung nakikinig lang sila pero hindi nila alam kung anong station. Lalo kung particular program lang ang pinakikinggan or pinanonood. Sabi ko hindi po ako taga DZBB. Taga DZRH po ako. Sumasagot kasi ako sa mga followers. Nung sumunod, pinipilit na niya na taga DZBB ako, sabi ko hindi nga po. Hindi kasi siya araw-araw eh. Parang sudden lang, biglang lang sila nagpopop up sa msgr, sila sila ulit. tapos sasabihin naman nila na: oras na ng programa ni kisses jabson kasama si orly mercado. Sabi ko ‘Wow, Orly Mercado.’ Sabi ko ‘Hindi nga po ako taga-DZBB. Baka po iba po ‘yung tinutukoy ninyo, hindi po ako’ Pero pinipilit nila.” Kisses Jabson, DZRH Anchor, reporter, writer

Kisses Jabson, DZRH Anchor, reporter, writer

As an anchor, reporter, and writer at a local media outlet, Jabson has a Facebook page with 4,700 followers, as of writing. According to her, she preferred a public page because of the nature of her work. She maintains regular interaction with listeners and patrons of her show through her Facebook page.

Photo Credit: Kisses Jabson

As a public figure, it was normal for her to receive messages from followers. But this incident was different.

Jabson said that these messages kept coming so frequently that she lost count of how many people sent her the same message—a promotion about a radio program on another station she was allegedly hosting.

She denied such information.

“Ako, napipikon din, kasi syempre pinagtatanggol ko na hindi ako doon, plus yung station ko pinagtatanggol ko rin,” she said in an interview.

Kisses Jabson

It was not a big deal at first but these accounts took it a step further, sending the same message to her workmates. This bothered her thinking that the false information might reach her bosses who might think that she had intentions of transferring to another network.

Jabson thought that it was possible that these accounts were fake. The messages were the same and the accounts used names of veteran anchors and reporters whom, according to her, would not send her such messages.

Until now, she has no idea as to who the people behind these accounts really were, and why they were sending her these messages. She could not think of anyone who could hold a grudge against her and do this as revenge.

Despite the anxiety brought about by this experience, Jabson did not report the incident to the authorities.

“Kaya lang hindi kaya masyadong mababaw pa yung sitwasyon para ipa-NBI since mas maraming problema ang NBI na mas mabigat kesa dun sa ‘kin,” she said.

She also mentioned that based on her experience, the country’s existing laws need to be emphasized to the people, to get them informed of their rights and possible actions when being victimized online.

“Yung iba baka mayroon nakaka-feel ng threat sa kanilang buhay na mas matindi pa sa experience ko pero hindi sila makapagsalita kasi hindi nila alam kung saan sila magsusumbong.”

According to her, people lack information about the existing laws that could protect them from online crimes such as fake news.

“Although aware ang mga tao na merong Anti-Cybercrime Law, hindi masyadong nabibigay ‘yung information kung ano ba ‘yung lawak, sino ba ‘yung pwedeng magreklamo, ano ba ‘yung reach nung mga complaints na pwede ibigay sa kanila, paano pupunta sa kanila, sino ‘yung kokontactin na mga tao,”

Jabson called for the government to have better information dissemination on where, how, and to whom people could report when falling victim to fake news.

“Siguro magkaron tayo ng mass information, mas magreach tayo sa mga tao yung ating mga ahensiya ng gobyerno kung sino ba yug pwede lapitan. Pwede bang pulis? Kasi baka mamaya unjust vexation, hindi mo naman kilala kung sino idedemanda mo diba.”

Kisses Jabson, DZRH Anchor, reporter, writer

And vloggers, too

Vlogger Yasmin Asistido’s wide reach and thousands of followers seemed to put her at risk of fake news as well.

Yasmin Asistido, more commonly known as Kween Yasmin, is a vlogger with more than 101 thousand Youtube subscribers and 292 thousand followers on Facebook. She describes herself as a vlogger, content creator, singer and composer.

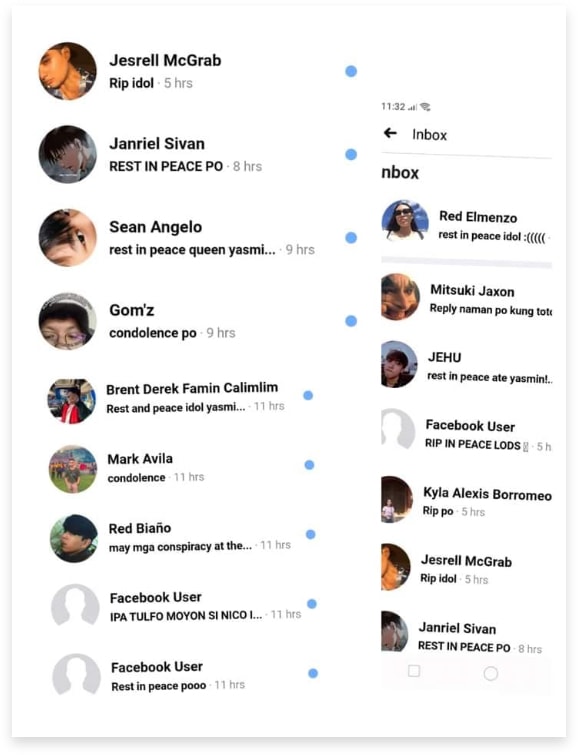

During the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic around March, Yasmin received a message from a friend that someone had posted on Facebook that she tested positive for COVID-19.

She personally saw the post which seemed to be a screenshot of a news report. The imaged showed her lying on a bed with the logo of a big news outlet on the side and the logo of a news program at the bottom.

Yasmin denied this and said that it was fake.

“Hindi naman po totoo. Masakit po kasi pinagbintangan ka na may COVID kahit wala naman.”

Yasmin Asistido

According to her, the picture was grabbed from an audition video she posted on her Youtube page—a public account. The logo of the news program was fabricated and placed on the photo to make it appear like it was a legitimate news report.

This photo became so viral that a lot of concerned people messaged her and wished her well. Others thought she had died.

Because of this incident, Yasmin was not able to create content for one week. Creating and uploading videos online is her major source of income.

Like Jabson, Yasmin also refused to report this to the authorities. Instead, she merely brushed off the incident, thinking that if she does not give much attention to these fake posts, they would stop.

“Dinedeadma ko na lang po sila, ‘di ko na lang pinapansin. Ignore and delete. Kasi kapag pinansin lalong magpapatuloy sila. Gagawa ng fake news.”

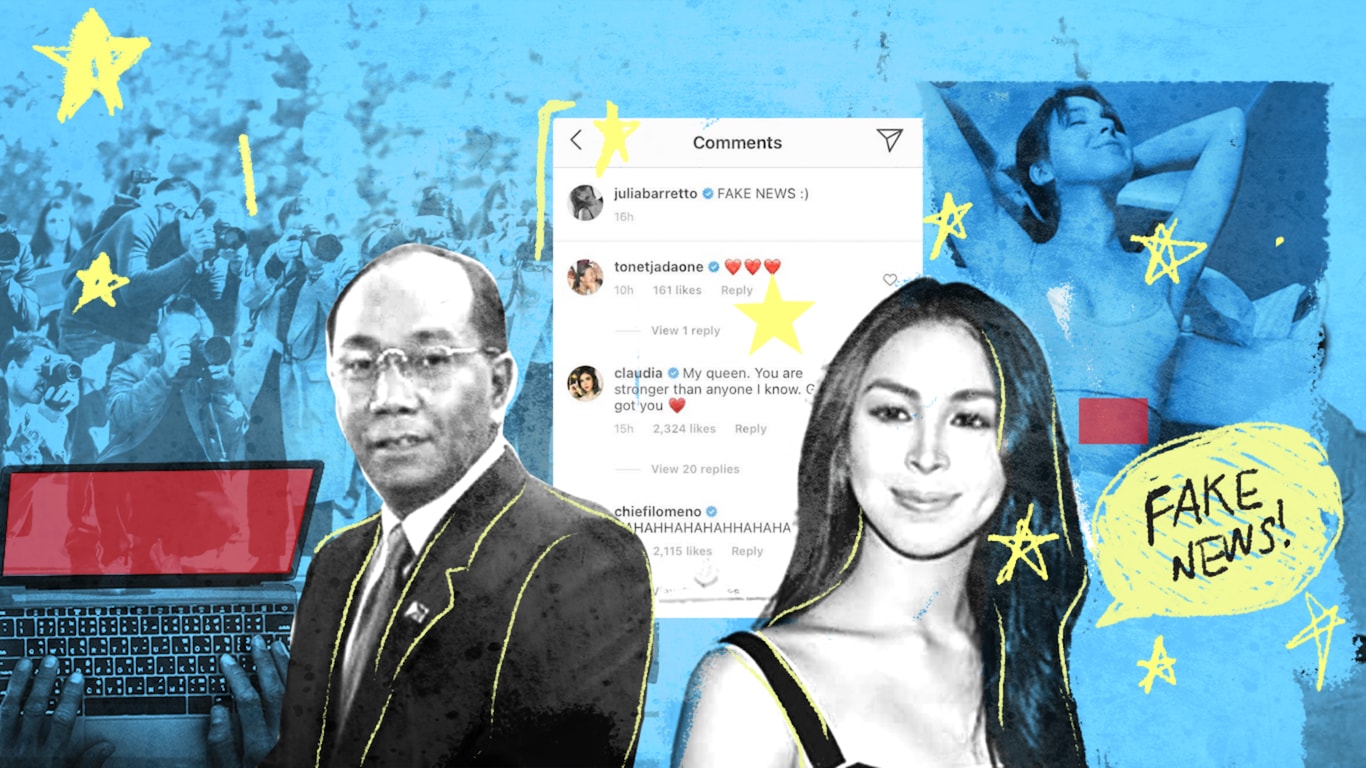

Celebrity fights back

In September 2020, former broadcaster Jay Sonza claimed through a Facebook post that Julia Barretto was pregnant with Gerald Anderson’s child. After a few days, Barretto denied the allegation and filed a complaint with the NBI about the fake and irresponsible post of Sonza.

One of the most beautiful faces in showbusiness, Barretto accused Sonza of cyberlibel and violation of the Safe Spaces Act.

Barretto said in an interview that she had encountered a lot of fake reports circulating around social media and she had to stand up for herself this time to put a stop to fake allegations.

“Ang dami ko na rin kasing pinagdaanan, marami na rin akong pinalampas lalo na sa social media. Binastos na ‘yung reputation ko, ‘yung pangalan ko. And you know I think I just want to show people now na hindi ko na pinapalampas ‘yung mga bagay na ganito,” Barretto said.

Sonza soon deleted the post on his Facebook page.

Barretto was proud of defending herself this time. She said she was ready now to fight purveyors of fake news online.

“I was proud of myself because, for the first time, I stood up for myself. For the first time, I defended myself. And for the first time, I protected myself.”

Julia Barretto

“I’m putting my foot down and showing people that enough is enough. I can’t tolerate fake news anymore especially involving me or my family and anyone close to me,” she added.

Barretto said it was important to confirm any information from the people involved before spreading it, especially something as delicate as involving one’s pregnancy.

“If you were to confirm something like that, it’s not supposed to come from you. It’s always supposed to come from the people who are involved: somebody close to me, from a family member, from a friend,” she said.

Cascolan’s accounts?

Facebook had to shut down three fake Facebook accounts associated with former PNP Chief Camilo Cascolan upon PNP’s request.

Facebook accounts with names: "Camilo Pancratius Pikoy Cascolan", "Camilo P Cascolan", "Camilo Cascolan" were misrepresented to be owned by the ex-PNP Chief.

These poser accounts were found to be involved in online swindling, estafa, and solicitation of funds from victims purportedly for social welfare and humanitarian projects. The fake accounts were also involved in social networks enticing Facebook users to donate funds for computer tablets for students in urban poor communities for online classes.

Cascolan warned the people against using his name for illegal activities that the anti-cybercrime group will be looking after them.

Facebook has shut down these accounts as requested by PNP. Four persons of interest have already been under investigation.

Are you with us so far? Let’s check.